Reviewing Poetry Translations

Years back, I reviewed a number of translations: Hungarian-translated-into-English books. Mostly poetry. While I feel comfortable reviewing poetry in English, I realized how important to know Hungarian culture and history is. I know bits of their culture and history, but I’m not even close to what any high school kid in Budapest knows.

Reviewing a culture’s poetry to which I am not richly connected to, will, by default, be difficult.

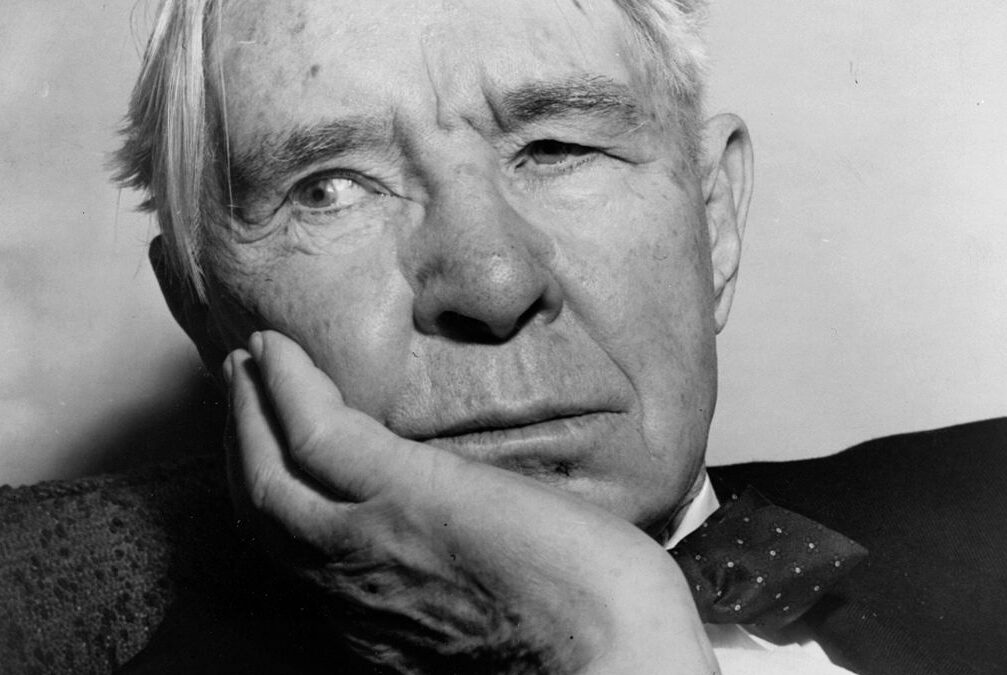

Let’s look at a poet who is considered about as American of a poet as it gets:

Carl Sandburg in Context

For example, a non-American reviewing Carl Sandburg would need to know he was not a communist in the same sense as a leader in 1960s Russia, but a capitalist in the Midwestern United States. There were things he appreciated, but he would not have applauded how Russia treated dissidents. The dissidents were his peers, not his enemies. When he wrote with communist intonations, he wrote in a context that was Democratic, freethinking, and, from his opinion, required improvement, not eradication.

The translator would also need to know what it was like to watch a city grow before him. When he wrote three urban-focused collections of poetry: Chicago Poems, Cornhuskers, and Smoke and Steel, he was living in the Chicago area. Chicago in 1920 was still rebuilding from the massive 1871 fire that destroyed one third of the city. The Industrial Revolution was long over, but the impact on Chicago manufacturing continued. Sandburg saw this and more.

Context changes our read and understanding of poetry so connected to a city and timeline as was Sandburg’s. The poetry lives on because what was happening then in many ways is universal. The human effort to build a city can be seen in Dubai, Beijing, and Baghdad. However, any translations of his work can only succeed if they can understand Sandburg’s Chicago.

That’s not even getting into the troubles for an average poet to translate a known master.

Mostly, I read the works of Hungarian masters translated by academics not known for their own poetry. While they gave it a great effort and further exposed great Hungarian poets to the non-Hungarian speaking world, the result was often arrhythmic or lacked heart.

While I deeply wanted to support any outreach of the Hungarian culture into the English speaking world, giving a positive review wasn’t always possible.

Charles Baudelaire and Poe

Charles Baudelaire famously translated Edgar Allan Poe’s work into French from 1852-1865 (Poe died in 1849). It worked because of two reasons: Baudelaire was a top rate poet in French; he was a passionate fan of Poe’s work. He understood Poe’s work intimately. He understood Poe’s romantic heart, addictions, and sense of loss. They were brothers in his way.

Nuance was not lost on him or in his translation. Most of his translations were of fiction, but his translation of “The Raven” received the most acclaim. The source material was superb, and the translator more than capable.

When he published the work, Poe’s reach extended wherever French was read. That’s rare. I’d love to see this sort of thing expand. Great poets translating great poets.

More:

photo: public domain. – Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.